Large numbers of previous studies have considered the use of domains intended to cause confusion with the names of official and trusted sites, as a means of launching fraudulent attacks or creating other kinds of infringement. Indeed, this is one of the primary factors behind the importance of online brand protection.

In many cases, these types of attack are successful because of a lack of understanding by general Internet users of the structures of URLs (web addresses) and the significance of the contexts in which particular characters (such as dots / periods (‘.’), slashes (‘/’) and hyphens (‘-‘)) can be used. With this in mind, previous articles have considered a number of ways in which domain-based fraud can be conducted, including the use of subdomain names together with unbranded hyphenated domain names (e.g. a URL such as bankbrand.co.uk-account.help to impersonate bankbrand.co.uk/account-help)[1], use of subdomain names together with truncated brand domains (e.g. g.oogle.com in place of google.com)[2], hyphenated branded domain names intended to resemble official URLs broken across line-breaks – particularly when displayed on mobile devices (e.g. account.financebran-d.com)[3], and deceptive domains with names beginning ‘www’ or ‘http’, to create confusion with full URLs[4].

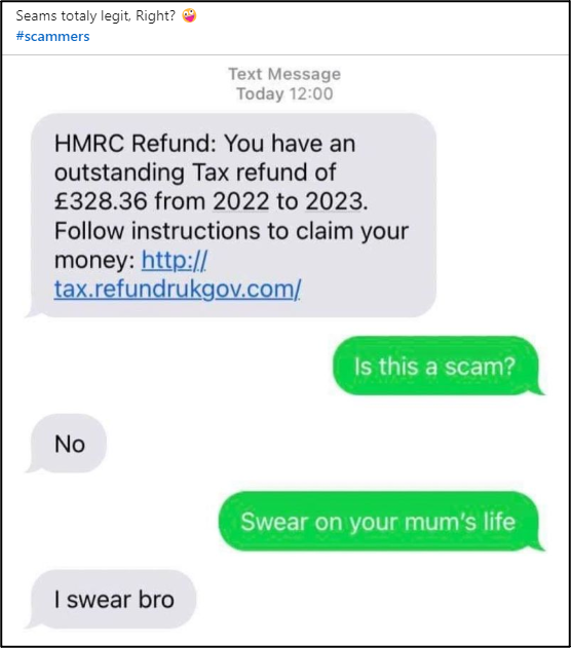

In this study, we consider domains intended to produce confusion with official UK government websites, which are generally hosted on .gov.uk domains, inspired by a screenshot of a light-hearted text-exchange with a scammer, posted on LinkedIn[5] (Figure 1). Government websites can be an attractive target for bad actors, as they are generally high-profile, well-used sites, and frequently incorporate a transactional (financial) element. Many members of the public will be familiar with these types of scam through communications received by e-mail or on mobile devices.

Figure 1: Posting including a screenshot of an SMS-based scam utilising a domain name impersonating a UK government website

Based on zone-file information available through ICANN’s CZDS service as of 12-Jan-2024, there are 321 registered gTLD domains with names containing ‘uk?gov’ or ‘gov?uk’ (where ‘?’ is an optional extra character, in each case). Of these, 152 are considered to be ‘high-risk’ in terms of potential intent for confusion with official .gov.uk sites (i.e. neglecting non-sensical domain names or instances where the terms appear in other contexts such as the explicit string ‘uk(-)government’ or ‘gov(...)ukraine’).

14 of the 152 domains appear to be registered to official government departments, potentially as defensive registrations, many of which (in accordance with good domain ‘hygiene’ practice) are configured to re-direct to official websites, though this still leaves a significant majority of the domains registered to third parties.

Within the set of 138 third-party, high-risk domains, a number of recurring themes and patterns are present. There are several keywords suggestive of intended use in scams which appear within the SLDs (second-level domain names; the part of the domain name to the left of the dot) multiple times, including ‘HMRC’ (6 instances), ‘DVLA’ (6), ‘debt-relief’ (4), ‘visa’ (3), ‘homeoffice’ (3), and ‘rebate’ (2). It is also notable that several of the domains utilise new-gTLD extensions which have been commonly linked with non-legitimate activity[6],[7], including .top (8 domains), .site (6), .online (6), .shop (6), .xyz (4), .cloud (2), .digital (2), and .live (2). A number of other concerning TLDs also feature just once within the dataset, namely .tax, .works, .chat, .date, .wtf, .agency, and .lol. Also of significance is the prevalence of use of retail-class registrars in the domain registration dataset, also previously noted as being popular with infringers[8], with a list topped by GoDaddy.com, LLC (18 domains), Namesilo, LLC (9), and Amazon Registrar, Inc. (9). Finally, of the 118 domains for which whois information was available via an automated look-up, 97 (82%) explicitly make use of privacy-protection service providers, as is common for infringers wishing to hide their identity.

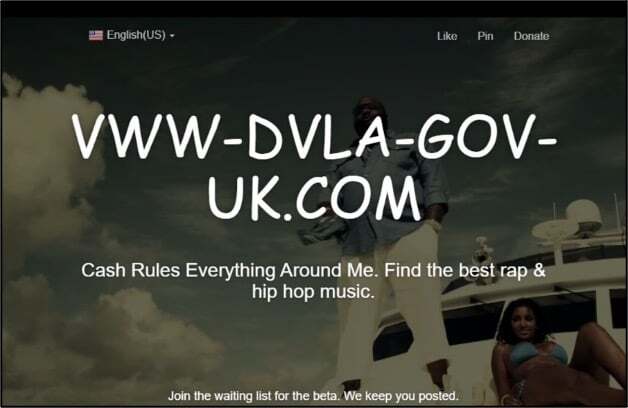

Considering the content of the websites in question, the domains resolve to a range of page types, including several resolving only to parking pages or no live content, but which may warrant further monitoring for changes to content, or might potentially be being used for their e-mail functionality (e.g. in phishing attacks) – in fact, 57 of these sites (41%) have active MX (mail exchange) records, indicating that they have been configured to be able to send and receive e-mails. Even more concerningly, four of the domains generate browser warning pages that fraudulent or otherwise dangerous content is (or was formerly) present, and a small number of examples were found to resolve to fraudulent or other concerning live content as of the date of analysis (13-Jan-2024) (Figure 2).

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Figure 2: Examples of live sites of concern, with SLDs as follows:

- pay-uk-gov (a site offering ‘credit’ services to a French audience);

- govukvisa (a Chinese-language site displaying ‘UK Visas and Immigration’ branding);

- homeofficegovuk (a partially-constructed site purporting to relate to ‘UK Visa and Immigration’);

- vww-dvla-gov-uk (a partially-constructed site currently with non-relevant content, but featuring a ‘donate’ link

The significant number of infringements – combined with the presence of a number of scam sites which are still live as of the time of analysis – shows the extent to which the government is targeted by these types of scam. The findings highlight the importance of official organisations, trusted entities and other brand owners putting in place proactive programmes of brand protection – consisting of both monitoring for the appearance of new infringements, and enforcement actions to take down threatening content, combined with ongoing monitoring of dormant content, to detect any subsequent appearance of material of concern – in addition to other measures such as defensive registrations and (where appropriate) the maintenance of relevant portfolios of protected IP. These measures can help protect the reputations of the organisations in question, and defend customers from the effects of fraud and other attacks.

[1] https://circleid.com/posts/20220504-the-world-of-the-subdomain

[2] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/exploring-domain-hostname-based-infringements-david-barnett/

[3] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/hyphenated-domain-infringements-david-barnett/

[4] https://circleid.com/posts/20220913-registration-patterns-of-deceptive-domains

[5] https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7151327407482847233/

[6] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/expert-.watches-.new-.online-.website-.news-.lol-a-review-of-the-current-state-of-the-new-gtld-programme

[7] https://circleid.com/posts/20230117-the-highest-threat-tlds-part-2

[8] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/web-dot-coms-but-once-a-year-holiday-shopping-activity-part-1-black-friday-domains