Fair use has never been so fashionable.

You will have heard it being cited time and again as a defence in the ever-increasing list of AI copyright lawsuits in the US, the most recent being the lawsuit brought by the New York Times (NYT) against Microsoft. NYT has alleged that Microsoft infringed the copyright in many of its news articles, opinion pieces and investigations by using them to train the Chat GPT and Copilot large language models.

To recap the battle lines: Microsoft thinks that the way it uses NYT content falls within the US defence of “fair use” because it serves a new, “transformative” purpose. If you ask NYT: "there is nothing 'transformative' about using The Times's content without payment to create products that substitute for The Times and steal audiences away from it”. Ouch.

So what is fair use - and why are we talking about transformation?

There has been a lot of discussion around fair use in the US, where it is a standalone defence to copyright infringement. There are four statutory factors which the US courts consider when determining whether a use is “fair”: its purpose and character (including whether that purpose is transformative); the nature of the original work; the amount of the original work which has been taken; and the effect on the market for the original work.

There have been some big decisions from the US courts recently regarding the first factor (purpose and character). The first factor is important because it goes to the heart of copyright. The theory is that without a safe harbour for “transformative” versions of existing works, which demonstrate a new purpose and character, we stifle creative inspiration. How the law understands transformation will have big repercussions for both US and UK copyright law as it applies both to human artistic works and to the outputs of AI models.

But why is fair use relevant to UK copyright infringement?

There are a group of well known “fair dealing” exceptions under the Copyright Designs and Patents Act, which we usually remember with reference to their purposes: research, private study, criticism, news reporting, parody etc. It’s easy to forget that as well as determining whether the purposes are established, UK courts will also be looking at whether the dealing for those purposes has been fair.

Unlike in the US, the UK has no statutory criteria of fairness. The applicable tests have been developed through case law, but (perhaps unsurprisingly) they have ended up incorporating several considerations similar to those included in US legislation. For example, both the US and the UK courts will consider the purpose of the later work and the extent to which it competes with the way the work is (or could be) used by the copyright owner. This is why the recent US decisions on fair use are so interesting.

So, what was decided?

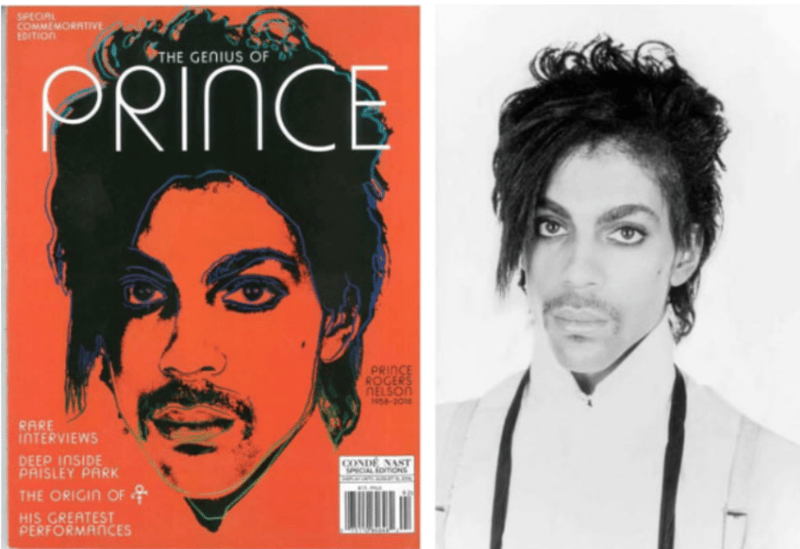

The copyright infringement case against Andy Warhol by Lynn Goldsmith (the woman who took the iconic shot of Prince used in Warhol’s series) came first. In May 2023, the US Supreme Court decided that adding new expression, meaning or message on top of an existing work doesn’t necessarily mean it has a purpose and character which is distinct from the original. Even if there are stylistic differences in the later work, where a commercial work shares a highly similar purpose to the original, it mitigates against the fair use defence being applicable. As a result, Warhol’s Prince series was found not to be a fair use of Lynn Goldsmith’s original copyright work.

This was a controversial decision. The two dissenting judges in the Warhol case didn’t hold back – pronouncing in their judgment that the ruling would “stifle creativity of every sort”, “impede new art and music and literature” and “make our world poorer”.

Warhol's "Prince" (left) and Goldsmith's original photo (right). Source: Court Documents

Is that really the case?

Shortly after the Warhol case was decided, we got a chance to test the predictions of the dissenting judges.

Famous tattoo artist Kat Von D was being sued in California by the photographer of the iconic Miles Davis portrait that she inked on a friend’s arm in 2017. The US courts had initially decided that the changes she made to create the tattoo were sufficient to give it a meaning and purpose which was distinct from the original portrait. It was big news then when in October 2023 (on a request for reconsideration of summary judgment) the California District Court reversed its initial finding on this point in light of the new position established in the Warhol case.

Kat Von D’s Miles Davis Tattoo - Source: Court Documents

The court’s previous decision in the Kat Von D case had taken into account stylistic factors, such as the fact that the inked version of the photograph added “movement” and a “melancholy aesthetic”. In view of the Warhol decision the court took a different approach, focusing on whether the overall use revealed a transformative purpose, and eventually deciding that there was not enough evidence to support this.

What does this mean in practice?

It appears that arguing stylistic and artistic differences is no longer enough to get a foothold on the ladder of fair use, if you can’t argue that the later work serves a new purpose.

It makes sense that the courts are keen to define the boundaries of the fair use defence and emphasise the need for a new purpose which goes beyond mere stylistic changes. Requiring a distinct (for example parodic) purpose is a clear statement that restating existing works is not enough – to be endorsed by the law, derivative works should advance the progress of science and the arts in some new way.

Understandable as they are, these changes will still have implications. Two immediately spring to mind in the context of the issues discussed above:

- Small(er) artists – although it is possible for Warhol and other world-famous artists to get the legal advice they need to come within this new, narrower reiteration of the fair use defence (and defend themselves when this is disputed) what does it mean for smaller artists? It is possible to imagine a world where the new, restated fair use defence doesn’t provide them with the security they need to create derivative works - where their creativity is stifled because it’s just not worth them taking the risk.

- AI creations – AI developers have put a lot of emphasis on how amendments to existing works constitute sufficient ‘transformation’ to bring them within the doctrine of fair use. But after Warhol, the courts are clear that adding new expression, meaning or message to an existing work is not enough. Will Microsoft and other gen-AI players be able to advance a convincing argument that the works created by their models serve an independent purpose when compared against the original works on which they were trained?

As we enter 2024, it seems that fairness has had a glow up - just in time for its big moment in the AI spotlight. I'm interested to see how fair it shapes up to be in practice.

Send us your thoughts:

Would you like to read more articles like this?

Building 1000

Cambridge Research Park

CB25 9PD

Fax. 01223 425258

info@iamstobbs.com

Privacy policy

German office legal notice

Cookie Declaration

Complaints Policy

Copyright © 2022 Stobbs IP

Registered Office: Building 1000, Cambridge Research Park, Cambridge, CB25 9PD.

VAT Number 155 4670 01.

Stobbs (IP) Limited and its directors and employees who are registered UK trade mark attorneys are regulated by IPReg www.ipreg.org.uk