A decision that caught our eye during the second half of 2023 was Audi & VW v Fruugo[1] before the District Court of the Hague (‘the Court’).

This was the first decision of an EU national court to consider the liability of e-commerce marketplaces offering unauthorised third party products since the CJEU, Europe’s highest court, answered a preliminary reference by two national courts in Louboutin v Amazon[2] (‘Louboutin’). The Louboutin case centred around Amazon’s liability for the advertising and storage of Louboutin shoes without the IP owner’s consent.

BACKGROUND

Fruugo is an online marketplace platform that operates in 46 countries. Third party sellers can retail their products on Fruugo, which offers a raft of ancillary services as part of the proposition. Fruugo does not directly sell products itself, instead advertising and hosting a platform under the FRUUGO umbrella brand.

VW and Audi (‘VW’) notified Fruugo of the counterfeit product on their platform. Fruugo removed the listings from their marketplace, but refused to pay any damages or costs to VW on the basis that it was merely the middle man who was not accountable for the actions of third party sellers on its platform. This is a common riposte from e-comm platforms when notified of counterfeits on their site.

VW brought court proceedings in the Netherlands for summary judgment, damages, and costs.

The Dutch court had two questions to decide:

- Was Fruugo itself using the VW trade marks, such that it directly liable for trade mark infringement by offering counterfeits on its platform?

- Was Fruugo indirectly liable as the middleman for hosting the counterfeits, or could it relying on the ‘hosting’ defence?

Image one: Fruugo NL homepage

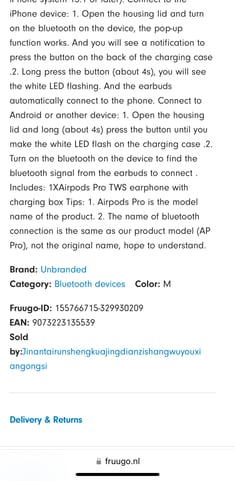

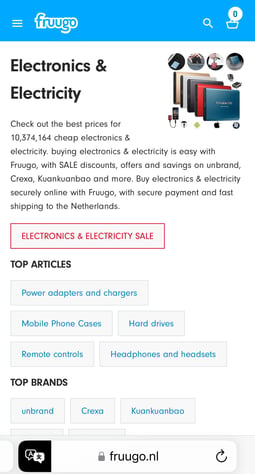

Image two: Electronics index listing page

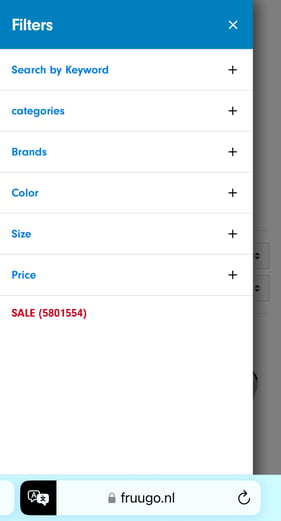

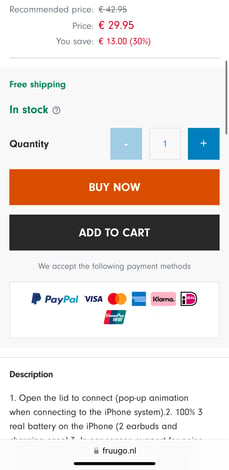

Images three, four, five and six: Index page filter- product listing page (shortened - seller details far down the page and after 'buy now' options)

FRUUGO: TRADE MARK INFRINGEMENT

Decision

Article 9(2) of the European Union Trade Mark Regulation (EUTMR) states that any unauthorised use of a trade mark, including that which may cause a likelihood of confusion among the public, constitutes trade mark infringement. Benelux law contains a similar provision.

Importantly, “use” is not defined strictly under the EUTMR or national EU Member State legalisation. This is intentional so that courts can be flexible and develop the definition via case law based on technological developments and the facts of a specific case.

The EU case law on direct trade mark infringement on e-commerce marketplaces goes back more than a decade (see L’Oreal v eBay (C‑324/09)) and, more recently, and Coty v Amazon (C-567/18)). The general principle is that marketplaces are not directly using third party trade marks where it is a third party selling retailing the product provided that the marketplace or other intermediary merely creates the technical conditions for use of the signs, allows their use and receives payment.

Louboutin moved things on somewhat, with the CJEU deciding that use of a third-party trade mark on an e-comm platform could constitute trade mark infringement by the platform itself if the product advertisements would be likely to give an informed user the impression that the operator itself markets, in its own name and on its own account, the goods bearing that sign, rather than a third-party seller; put another way, the online marketplace would need to exhibit active conduct to use the trade mark in its commercial communications.

In the present case, the Court found that Fruugo was not liable for trade mark infringement and distinguished its operations and use from Amazon’s in the Louboutin case: Fruugo did not sell product itself on its platform or fulfil shipment of third party orders. As such, it concluded that consumers would not think that there was any active sale by Fruugo themselves.

Analysis

Background

Fruugo operates in 42 countries and accepts 31 different currencies, taking 15% of each sales transaction. Fruugo’s pitch is seemingly not that it merely offers the requisite technical conditions to conduct a commercial transaction, but that through its technology and its umbrella ecosystem (including the FRUUGO brand) sales will be fortified.

A review of Fruggo’s own marketing material demonstrates the breadth of the offering, including:

- automatic product translation into 28 languages

- a dedicated customer care team

- a FRUUGO-branded customer care interface for buyer/seller

- four different shipment methods to choose from per territory

- product data ingested via feeds

- partnerships and e-commerce plug-ins for multiple leading platforms

- order management via either a Retailer Portal, Order API or via approved partners

Viewed individually, some of the above features may seem like routine e-commerce services. However, taking Fruugo’s operation as a whole, and when regard is had to certain features, the Fruugo marketplace is designed to maximise the sale of goods from the site, and Fruugo is doing much more than enabling customers to display signs on its marketplace. As such, Fruugo is not a primitive hosting provider or basic e-comm marketplace, where there would be a very clear distinction between technology backend and seller front end.

Fruugo’s store user interface also gives the impression of a singular, centralised marketplace to shop from, for example:

- the seller details (‘Sold by’) feature only on the listing itself, not the index page, and are hidden away at the bottom of the listing

- there is no ability to filter by seller when conducting a search

- contains product category claims such as

“Health & Beauty: Shop the best prices on 7,283,238 great value health & beauty. Shopping for health & beauty is easy with Fruugo, with SALE discounts, offers and savings on unbrand, Crexa, Robxy and more. Buy health & beauty online safely with Fruugo, with secure payment and fast shipping to (insert country).”

Average Consumer

To determine if there is confusion in the marketplace, courts notionally construct an average consumer, whose perspective is taken into account.

In Google France v Louis Vuitton Malletier[3] (Google France), it was established that the origin function of a trade mark is adversely affected by keyword advertising triggered by the trade mark if the advertisement does not enable reasonably well-informed and reasonably observant internet users, or enables them only with difficulty, to ascertain whether the advertised goods or services originate from the trade mark proprietor (or an economically-connected undertaking) or from a third party.

Courts have imbued the average consumer in an online space as being more aware of how e-commerce works, such as sponsored ads and organic search results on an internet search engine. Whilst that might have been true of a relevant consumer a decade ago shopping on a laptop or PC via an internet search engine, modern consumer habits are very different. Today, in many countries smartphones are the most common way for online purchases to be made[4], driven by social media ads, and completed via express payment methods such as Apple Pay and Google Pay.

A consequence of mobile-optimised websites and frictionless purchasing is that online consumers are sometimes less circumspect than they used to be, not more. This is important because a lower level of attention is more likely to give rise to a likelihood of confusion.

Use

A visit to the Fruugo website shows that the brand that consumers see when they search to buy on Fruugo is predominantly FRUUGO. and other product brands. This picture is different from the Fruugo seller page, which appears to have only been updated recently (December 2023). Of course, an average consumer of products on Fruugo would not visit such pages in the course of a retail transaction. The overall impression is also in contrast with marketplaces where there is a clearer delineation of sellers on the platform, such as eBay, Redbubble or Etsy.

Fruggo’s translation technology when used in conjunction with the FRUUGO brand is not just a mere passive background process, but active use to unlock, optimise and facilitate an otherwise unlikely sale. Furthermore, Fruugo was the main brand under which the goods were offered, with the dedicated customer care team available to field customer complaints about counterfeit product purchased from a relevant seller and provide a level of customer support. Fruugo would also share in any revenue raised from the VW counterfeits.

Taking into account the FRUUGO veneer and the average consumer, it is reasonable to envisage that a consumer would, at the least, have difficulty determining who is selling the product. There are parallels here with the Louboutin case, where the lack of delineation by Amazon on what was Amazon-retailed and third-party-retailed contributed to the potential for consumer confusion. Indeed, consumers seldom read the full T&Cs, which might contain some buried away caveats on a business model, operations, and who is being contracted with. The look and feel of Fruugo is such that a consumer receiving sub-standard product may hold their main grievance with Fruugo, not the individual seller. Indeed, details such as Fruugo-branded invoices would contribute to this post-sale.

The UK courts have taken a more progressive approach in recent times than the Court here (see Montres Breguet SA & Ors v Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd[5] involving Swatch and Samsung). There, the High Court and Court of Appeal both found that Samsung’s offering of watch faces on the Samsung Galaxy App store featuring the Swatch family of brands constituted direct use by Samsung itself. One factor weighing into this was Samsung’s material assistance to developers of watch face apps, not dissimilar to the suite of services offered by Fruugo (see above).

Furthermore, Fruugo specifically advertises the availability of a wide range of brands on its store, which it clearly regards as a feature worth promoting to would-be buyers and sellers, with a view to making the products retailed more attractive by virtue of being comprehensive.

When viewed in the round, Fruugo’s own use (and liability therein) of VW’s IP is more compelling than the Court gave credit for.

(2) INTERMEDIARY DEFENCE

The Court also had to decide whether Fruugo could benefit from an intermediary defence under Article 14 of the E-commerce Directive 2000/31/EC (the Directive). To satisfy the defence, Fruugo needed to show that it did not have actual knowledge of the third party seller’s infringing activity / content or upon becoming aware expeditiously removes it.

Decision

Article 14 of the Directive provides a ‘safe harbour’ defence from liability for hosting intermediaries. To benefit from the defence an intermediary such as Fruugo needs to show that it either doesn’t have actual knowledge of the illegal activity or, upon becoming aware of such activity acts expeditiously to remove or to disable access to the information.

Fruugo had removed the content quickly, so the focus was on Fruugo’s own role. The Court found that Fruugo did not have an active role because its advertising services were optional and formatted via technical and automatic processing, with the wraparound services by Fruugo (e.g., customer services, returns processing, translations and Fruugo’s logo being placed on invoices).

Analysis

The Court’s decision that Fruugo was merely a neutral hosting intermediary under the Directive does not sit right with this writer based on the facts of the case.

Whilst not privy to the evidence presented to the Court, the totality of Fruugo’s operation goes above and beyond what could reasonably have been expected when the legislation was enacted in the year 2000. For example, the Recital 42 to the Directive states that:

"The exemptions from liability established in this Directive cover only cases where the activity of the information society service provider is limited to the technical process of operating and giving access to a communication network over which information made available by third parties is transmitted or temporarily stored, for the sole purpose of making the transmission more efficient; this activity is of a mere technical, automatic and passive nature, which implies that the information society service provider has neither knowledge of nor control over the information which is transmitted or stored.”

This position was also echoed in L’Oreal v eBay:

“Where…the operator has provided assistance which entails, in particular, optimising the presentation of the offers for sale in question or promoting those offers, it must be considered not to have taken a neutral position between the customer-seller concerned and potential buyers but to have played an active role of such a kind as to give it knowledge of, or control over, the data relating to those offers for sale.” it cannot then rely…on the exemption from liability referred to in Article 14(1) of Directive 2000/31. (at para. 116)

“The operator plays such (an active) role when it provides assistance which entails, in particular, optimising the presentation of the offers for sale in question or promoting them.” (at para. 123)

As set out above (Analysis, Background), Fruugo’s ecosystem includes various ways to optimse listings. For example, language is one of the most fundamental elements of a sale, with the automatic product translation into 28 languages enabling a given listing to reach a much wider target audience. Similarly, a dedicated Fruugo customer care team exists to ensure that transaction are smooth and optimised.

Moreover, the CJEU in L’Oreal v eBay stated that intermediaries could not rely on the “hosting” exemption even in situations where they did not play an “active role” if they were aware of facts or circumstances which a diligent economic operator should have realised that the offers for sale in question were unlawful. Here, the enormity of the VW and Audi brands combined with the low-grade and wide-ranging products on sale should arguably have drawn Fruugo’s attention to the sales.

Overall, it is difficult to square the Court’s decision that Fruugo was a neutral intermediary against the facts of the case and the dicta of previous case law. What we appear to be left with is a have-your-cake-and-eat-it approach by more developed online intermediaries who advertise the sophistication of their services to would-be sellers, but then feign ignorance regarding the activities of their sellers when enquired upon by IP rights holders or the courts.

CONCLUSION

The application by the national Court here feels like a missed opportunity to help move on the case law in this area, some of which is over a decade old and limited to a specific retail model / environment. In a day and age where the legal ramifications of NFTs and AI are being grappled with, such as whether NFTs can constitute property[6] and the fiduciary duties of crypto platforms[7], decisions such as this one seem off-the-mark and outdated.

Online marketplaces have developed in sophistication since the turn of the 21st Century, with many falling somewhere between eBay (a third-party-only marketplace that is clearly predicated on individual sellers) and Amazon (a full sales and fulfilment ecosystem). The binary approach of the courts that a marketplace is one or the other (eBay or Amazon) fails to assess contemporary operations and how consumers would realistically perceive an online marketplace to operate. There is an undercurrent of placing undue emphasis on the technical mechanics of its operation in the background or caveats buried away in T&Cs, whereas a simpler holistic and contextual approach on how consumers would perceive the website would arrive at more pragmatic decisions being reached – arguably, frictionless retail has had the unintended consequence from an IP infringement perspective of making ‘morons in a hurry’[8] of all of us.

The Digital Services Act (‘DSA’) comes into force fully on 17 February 2024 and will apply to all online platforms. The DSA is designed to improve online safety for EU consumers, including protecting consumers from being exposed to counterfeit product. Proactive monitoring by platforms and enhanced reporting tools for consumers form key tenets of the DSA.

Whilst the DSA is intended to co-exist with the Directive, it essentially supersedes it by repealing and replacing Article 12 - 15 of the Directive[9], meaning that a different approach may be taken in future. For example, Article 6 of the DSA, which replaces Article 14, adds a further limitation to the hosting defence where a consumer would believe that the goods / services were “provided either by the online platform itself or by a recipient of the service who is acting under its authority or control” (see Art. 6(3)). It is hoped that this will place more emphasis in practice on the storefront’s appearance to consumers rather than the backend technical conditions that platforms use to defend claims currently.

We’ll be reporting more on the DSA over the coming months. However, as with all new legislation, it will take at least several years of case law to provide answers to some of the questions raised. In the meantime, brand owners should continue to pursue both counterfeiters directly as well as the platforms themselves, who are a linchpin within the infringement machine.

[1] C/09/622304 /1-lA ZA 21-1 105

[2] Cases C‑148/21 and C‑184/21

[3] [2010] ECR I-0000

[4] https://www.statista.com/topics/5888/mobile-commerce-in-the-uk/#topicOverview

[5] [2022] EWHC 1127 (Ch) and [2023] EWCA Civ 1478

[6] Lavinia Deborah Osbourne v Persons Unknown; Ozone Networks Inc [2022] EWHC 1021 (Comm)

[7] Tulip Trading Limited v Wladimir van der Laan and ors [2023] EWCA Civ 83

[8] Morning Star Cooperative Society Ltd v Express Newspapers Ltd [1979] F.S.R. 113

[9] See Article 89 (1)-(2) and Articles 4, 5, 6 and 8 of the DSA.

Send us your thoughts:

Would you like to read more articles like this?

Building 1000

Cambridge Research Park

CB25 9PD

Fax. 01223 425258

info@iamstobbs.com

Privacy policy

German office legal notice

Cookie Declaration

Complaints Policy

Copyright © 2022 Stobbs IP

Registered Office: Building 1000, Cambridge Research Park, Cambridge, CB25 9PD.

VAT Number 155 4670 01.

Stobbs (IP) Limited and its directors and employees who are registered UK trade mark attorneys are regulated by IPReg www.ipreg.org.uk