This article was co-written by Geoff Steward and Emma Dixon.

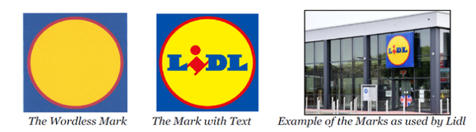

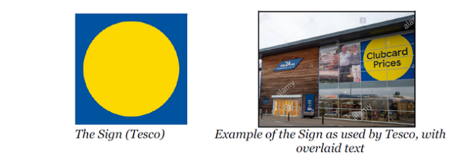

On 19 March 2024, the Court of Appeal upheld the High Court’s finding of trade mark infringement (and passing off) by Tesco in the highly publicised dispute between Lidl and Tesco, concerning Tesco’s use of a blue and yellow sign (the “Tesco Sign”) for its Clubcard promotions.

The Court of Appeal also dismissed Lidl’s appeal against the High Court’s finding of ‘evergreening’ by Lidl by way of certain trade mark applications which were found to have been made in bad faith by Lidl, and – to the relief of copyright lawyers – the Court of Appeal has overturned the High Court’s finding of copyright infringement. But it is the trade mark infringement by Tesco which is so interesting about this judgment.

In particular, in dismissing Tesco’s appeal against the finding of trade mark infringement, Lord Justice Arnold signposted the value of evidence on consumer behaviour when approaching trade mark infringement claims – thus demonstrating that the court’s direction of travel finally seems to be catching up with the science, something which readers may be aware we have been encouraging for over a year since the publication of ‘The Psychology of Lookalikes’.

A ‘substantial’ u-turn on copyright

At first instance, Smith J found that: (1) the Lidl Mark with Text (the “Lidl Work”) was an artistic work protected by copyright; (2) Lidl established a presumption of copying, which Tesco failed to discharge; and (3) a substantial part of the Lidl Work was reproduced in the Tesco Clubcard Sign with Text (the “Tesco Work”). This decision received a critical reaction from many legal commentators, particularly in respect of the finding of substantial reproduction.

The first instance judgment did not go into a detailed analysis on ‘substantial part’. The basic test of substantiality under UK law is whether the later work replicates a substantial part of the aspects of the earlier work which (by reason of the skill, labour and judgment which went into their creation) make it an original work attracting copyright protection. It was unclear to legal commentators how the judge found that a yellow circle on a blue square was a substantial part of the skill and labour of a work containing a complex logo design where the word, and font for, LIDL was a key element of the artistic work.

Tesco appealed against the judge’s findings on subsistence and on substantial reproduction and the appeal on the latter was allowed.

Lord Justice Arnold found that the judge had applied the correct test as to subsistence and that her conclusion that the Lidl Work had “involved free and creative choices so as to stamp it with the author’s personal touch” was a conclusion open to her.

However, on his analysis as to substantial reproduction, Lord Justice Arnold concluded that Tesco had not infringed copyright in the Lidl Work. Counsel for Tesco submitted that Tesco had not reproduced a substantial part of that copyright work because Tesco had not copied what was original to the author(s) of the Lidl Work. He pointed out that the shade of blue in the Tesco sign had been used previously by Tesco as part of its corporate livery, Tesco had previously used yellow circles in their signage, and the distance between the yellow circle and the edges of the blue square in the Tesco Signs was different to the Lidl Work. It followed, he argued, that all that Tesco’s design agency had copied from the Lidl Work was the idea of a yellow circle in a blue square.

Lord Justice Arnold found that although the Lidl Work is sufficiently original to attract copyright, the scope of protection conferred by that copyright is narrow. He found that Tesco had not copied at least two of the elements that make the work original, namely the shade of blue and the distance between the circle and the square, and that although Tesco had copied the visual concept of a blue square surrounding (among other material) a yellow circle, that is all they had done. Overall, he concluded, this did not amount to copyright infringement.

Tesco’s trade mark infringement

At first instance, the Tesco Sign and the Lidl Mark with Text were held to be sufficiently similar when considered from the point of view of an average consumer. Despite the differing texts on the marks, it was held that these did not have the effect of “extinguishing the strong impression of similarity conveyed by their backgrounds in the form of the yellow circle, sitting in the middle of the blue square”.

The substantial evidence put forward by Lidl was held sufficient to establish a link between the Mark with Text and the Tesco Signs, with both origin and price match confusion/association found. There was no finding of a subjective intention on behalf of Tesco to deliberately take unfair advantage or ‘free-ride’ on Lidl’s reputation, as Tesco had simply been promoting its own agenda, but intention is not necessary for s.10(3) infringement.

Smith J held at first instance that use of the Tesco Signs had resulted in detriment to the distinctive character of the Mark with Text, as evidenced by the fact that Lidl had been forced to take ‘evasive’ action in the form of corrective advertising. Tesco was further held to have taken unfair advantage of the reputation in the Lidl Marks for low-priced value. She further held that Tesco had failed to establish due cause through its argument that it had the right to use a combination of yellow and blue colours, as yellow was commonly used by supermarkets as bright, attention-grabbing signage and blue is its own livery colour. Smith J stated that it was those characteristics used in combination that are specific to the Lidl Marks.

Tesco’s principal ground of appeal against the judge’s finding of trade mark infringement and passing off was that the judge was wrong to find that the average consumer seeing the Tesco Signs would be led to believe that the price(s) being advertised had been “price-matched” by Tesco with the equivalent Lidl price, so that it was the same or a lower price.

In dismissing Tesco’s appeal on trade mark infringement and passing off, Lord Justice Arnold noted that while at first sight the trial judge’s finding that a substantial number of consumers would be misled by the Tesco Signs into thinking that Tesco’s Clubcard Prices were the same as or lower than Lidl’s prices for equivalent goods is a somewhat surprising one. However, he went on to explain that the decision is perhaps less surprising when it is borne in mind that the judge had found on the evidence that: (a) the Wordless Mark had become distinctive of Lidl through use of the Word with Text; (b) that the Tesco Signs would call the Mark with Text to mind, and (c) and that it is common ground that Lidl have a reputation for low prices. Lord Justice Arnold concluded that the judge’s finding was based upon these three strands of evidence and that she was not only entitled to place some weight on each of those strands, but also to regard each of the three strands as reinforcing the other two. Ultimately, he concluded that “Standing back, I am not persuaded that her finding was rationally insupportable”.

In respect of ‘due cause’, Lord Justice Arnold interestingly noted that: “It is difficult to see how use of a sign which takes unfair advantage of the reputation of a trade mark can be with due cause, although it is perhaps easier to see how use which is merely detrimental to the distinctive character of the trade mark may be. Nevertheless the legislation allows for both outcomes”. This suggests that arguments of ‘due cause’ are less likely to be successful in s10(3) unfair advantage claims, which is good news for brand owners who register their packaging livery and sue lookalikes for unfair advantage trade mark infringement.

What now?

It remains to be seen whether Lidl, as a serial packaging copyist itself, will see this judgment used by brand owners looking to tackle Lidl’s own lookalike products. Smith J’s findings at first instance that colour and shape were key features of the Lidl Marks, with the “Lidl” word being less of a differentiator, are invaluable to those pursuing lookalike claims.

This approach also supports the conclusions of a 2023 behavioural science literature review commissioned by Stobbs, ‘The Psychology of Lookalikes’, namely that colour, shape, and brand image rank before product name in what influences a consumer to identify and purchase a product. Furthermore, Lord Justice Arnold now appears to have opened the door by encouraging brand owners to lead consumer behavioural science evidence, when he notes, at paragraph 118 that:

“When deciding issues such as likelihood of confusion, it can be of value for the court to receive evidence as to the shopping habits of consumers of the relevant goods or services: for example, as to whether they are in the habit of reading the label on an item before selecting it for purchase or whether they simply rely upon the appearance of the packaging. This is not in itself evidence of confusion, but it may be evidence of circumstances giving rise to a likelihood of confusion.”

A call to arms for brand owners wanting to stop lookalikes, if ever we saw one…

Send us your thoughts:

Would you like to read more articles like this?

Building 1000

Cambridge Research Park

CB25 9PD

Fax. 01223 425258

info@iamstobbs.com

Privacy policy

German office legal notice

Cookie Declaration

Complaints Policy

Copyright © 2022 Stobbs IP

Registered Office: Building 1000, Cambridge Research Park, Cambridge, CB25 9PD.

VAT Number 155 4670 01.

Stobbs (IP) Limited and its directors and employees who are registered UK trade mark attorneys are regulated by IPReg www.ipreg.org.uk