This article was co-written by David Barnett, Bryn Anderson and Tosshan Ramgolam.

Introduction: brand strength and brand value

The value associated specifically with an organisation’s brand can be significant, typically comprising around 20% of total enterprise value when taken as an average across all industry sectors[1],[2]. A number of components contribute to the value of a brand, including the value of associated products and services, and the future potential for revenue generation. Additionally, infringement activity, and the remediating effects of brand protection initiatives, can greatly impact on brand value.

A brand valuation study can have a number of benefits to an organisation, including the capability to better inform trademark protection and licensing strategies, assisting with investment planning and budgeting, quantifying brand damages arising through IP abuse, facilitating access to financial credit, and as part of general valuation projects necessary for tax considerations or mergers and acquisitions.

The first stage in valuing a brand is often a brand strength analysis, which can also provide a basis for comparison against competitor organisations. The strength of a brand can also affect its ‘royalty rate’. This is essentially an input into ‘royalty relief methodology’ which aims to quantify the cost of licensing relevant IP if it were not already owned by the brand). It can also affect customer behaviours – and ultimately revenue – all of which feed into a full, formal, final brand valuation.

In this article, we present an overview of some of the components of a typical brand strength analysis.

Components of brand strength analysis

To a high level, a brand strength analysis might typically make use of some or all of the following inputs, each of which can be expressed as a numerical metric (and which can conveniently be displayed on a ‘brand scorecard’), with a weighting controlling the extent of contribution to the overall measurement index:

- Actions by the brand owner:

- Brand protection (including consideration of both strategy and execution):

- IP rights coverage

- Brand protection implementation (monitoring and enforcement)

- Brand marketing:

- Marketing budget

- Social media use and policies

- Impact of stakeholders:

- Customers:

- ‘Top-of-mind’ and prompted brand awareness

- Net Promoter Score (NPS) – a measure of likelihood of customer recommendation

- Customers:

- Brand perception – including consideration of the factors driving likelihood of recommendation, such as product features / performance, brand attributes, emotional drivers, etc.

- Media – online prominence and sentiment

- Corporate and Social Responsibility (CSR)

- Commercial / financial performance – revenue, revenue growth and profitability

Comments on some of the key components within this list are given below.

- Brand protection programme benchmarking

Measurement and benchmarking (against peer companies) of the effectiveness of an organisation’s brand protection programme can be a useful exercise in its own right, helping to identify what constitutes a ‘best-in-class’ programme, identifying gaps in the current programme, and encouraging internal stakeholder ‘buy-in’ for future initiatives.

Assessment might typically take account of the following characteristics of the programme:

|

Category |

Areas of competency |

|

Effectiveness of online programme (i.e. capability to detect and remove infringements from a comprehensive set of digital channels) |

e-commerce marketplaces |

|

Social media platforms |

|

|

Domain names and websites |

|

|

Effectiveness of offline programme (i.e. capability to seize infringing physical products and seek legal redress at source, destination, and transit locations) |

Litigation (against infringers) |

|

‘On-the-ground’ programmes (customs, law enforcement) |

|

|

Public Relations (PR) (programme success and market relevance, with a view to reducing overheads, improving enforcement outcomes, and increasing ROI through collaborative efforts with industry partners) |

Media coverage |

|

Trade association partnerships and memberships |

|

|

Coverage of IP protection portfolio (an IP-rights portfolio allowing effective action against counterfeits online and at offline source, destination, and transit locations facilitating the global trade in counterfeits) |

Coverage to implement effective online enforcement |

|

Coverage to implement effective offline enforcement |

|

|

Presence of IP ‘squatters’ in at-risk territories |

Examples of some of the considerations for each of the above characteristics are given below:

- e-commerce marketplaces – To what extent are infringing listings available on a range of core and emerging marketplaces? Of the listings returned in response to brand-specific searches, what proportion are genuine vs. (suspected) counterfeit goods? What should the relative weightings of the priority level / importance of each platform be?

- Social media platforms – To what extent are infringing posts / accounts visible on core platforms? How protected are key handles / usernames? Are official / authorised accounts verified?

- Domain names and websites – To what extent is the official portfolio consolidated with an enterprise-class (corporate) registrar? How many brand-specific, third-party domain registrations are there, and what is the breakdown by site content (e.g. official vs. scam / lookalike site)? What does the enforcement and dispute resolution procedure history look like?

- Litigation – To what extent is the brand taking litigation measures against infringers to gain favourable decisions, deter future infringements, and recover damages / lost profits?

- ‘On-the-ground’ programmes – To what extent does the brand have core marks registered with customs in key destination and source locations, to prevent the global movement of counterfeit goods?

- Media coverage – How well are brand protection successes communicated to, and reported by, credible IP media outlets?

- Trade association partnerships and memberships – To what extent does the brand collaborate with trade associations and platform-specific programmes vested in challenging intellectual property infringement?

- Coverage to implement effective online enforcement – To what extent does the brand have core marks protected (e.g. by appropriate trademarks) in key jurisdictions related to e-commerce activity?

- Coverage to implement effective offline enforcement – To what extent does the brand have core marks protected in key destination, source, and transit jurisdictions to combat counterfeits?

- Presence of IP ‘squatters’ in at-risk territories – To what extent are trademark squatters present in first-to-file jurisdictions known to be infringement hotspots (which facilitates the production and proliferation of counterfeit goods)?

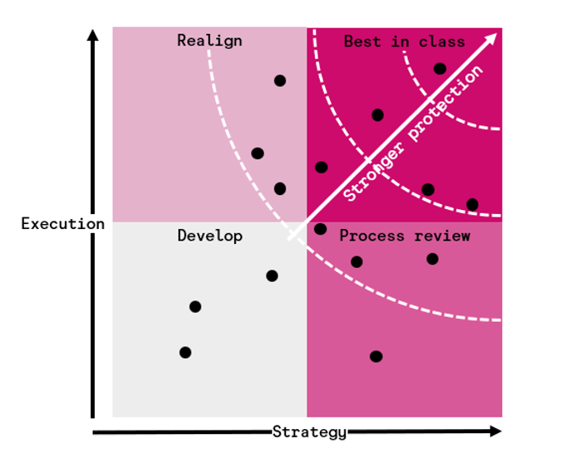

As part of the overall analysis, it may be appropriate to consider both the quality of the brand protection strategy itself (i.e. breadth of coverage demonstrating awareness of existing threats and ability to identify emerging threats), and the level of effectiveness of the execution of that strategy (i.e. demonstrable success in mitigating threats). Once these parameters have individually been quantified, companies can be benchmarked against each other by plotting their positions on a matrix, of which a schematic is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Strategy / execution matrix for brand protection programmes

Generally speaking, those brands with the most effective brand protection programmes will appear to the top-right of the plot area; broadly, the matrix allows us to split programmes into one of four categories:

- Best in class – Effective strategy, well executed (but still requiring ongoing oversight, to allow responsiveness to emerging threats)

- Requiring realignment – Often arising in response to a lack of updates to a previously effective and well-executed strategy

- Requiring process review – Reflecting shortcomings in the execution of the strategy, potentially reflecting an overall lack of investment in the programme, or a need to focus in higher priority areas

- Requiring development – Typically arising in cases where there has been insufficient stakeholder buy-in by the brand owner

- Online prominence and sentiment

Online brand prominence and sentiment can readily be metricised using approaches similar to those described in previous articles (e.g. looking at the top 100 global brands[3], fashion brands[4], cryptocurrency brands[5] and AI brands[6]), which allow comparisons between brands to be carried out. Broadly, the calculation is carried out through the use of sets of relevant search queries to generate ‘pools’ of candidate pages for analysis, and then counting the number and prominence of the mentions of each brand on each page, and the proximity to any of a library of keywords deemed to convey ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ sentiment.

Ongoing tracking

As an additional part of the analysis process of these metrics, and consideration of performance over time, it is possible to construct a series of brand protection / brand strength KPIs. These might typically include:

- General business-related metrics – e.g. such as sales volumes and revenue (overall, and by country)

- Online performance metrics – e.g.:

- Numbers of enforced infringements (by infringement type, country, brand, and/or product type)

- Compliance rate (by platform)

- Values of infringing items removed (potentially as part of a wider online BP ROI analysis)

- Offline performance metrics – e.g.:

- Numbers of civil / criminal enforcement actions

- Numbers and values of infringing items seized (by country, brand, and/or product type)

- Numbers of trademarks filed in relevant classes and jurisdictions

- Numbers of ‘overlapping’ third-party trademark registrations

Summary and discussion

Measurement of brand strength takes into account a number of components, and can form the basis of a subsequent full brand valuation calculation. The overall measurement index allows brands to be benchmarked against their competitors, and the individual components can also be compared between brands, to give a more granular analysis and identify specific areas where improvements can be made.

In general, we should expect a well-performing brand – i.e. one where the brand strength is high – to be associated with certain characteristics (in terms of the measurement metrics), such as high online prominence and (positive) sentiment, and low levels of infringements. Accordingly, it is important that the calculation framework is constructed in such a way as to correctly to reflect these points. For example, measurement of infringement levels should take account of the overall landscape, rather than simply considering (say) ongoing numbers of enforcements. For example, it may make more sense to incorporate data showing how the long-term trends have changed in response to the implementation of a brand-protection programme.

[1] https://www.iamstobbs.com/brand-protection-return-on-investment-ebook

[2] https://static.brandirectory.com/reports/brand-finance-gift-2022-full-report.pdf

[3] https://www.iamstobbs.com/online-brand-prominence-and-sentiment-ebook

[4] https://www.iamstobbs.com/measuring-brand-prominence-of-fashion-brands-ebook

[5] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/coining-success-trends-in-the-online-brand-prominence-and-overall-value-of-cryptocurrencies

[6] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/the-top-generative-ai-brands-in-2024

Send us your thoughts:

Would you like to read more articles like this?

Building 1000

Cambridge Research Park

CB25 9PD

Fax. 01223 425258

info@iamstobbs.com

Privacy policy

German office legal notice

Cookie Declaration

Complaints Policy

Copyright © 2022 Stobbs IP

Registered Office: Building 1000, Cambridge Research Park, Cambridge, CB25 9PD.

VAT Number 155 4670 01.

Stobbs (IP) Limited and its directors and employees who are registered UK trade mark attorneys are regulated by IPReg www.ipreg.org.uk