This article was co-written by David Barnett and Richard Ferguson.

Introduction

Following the announcement by ICANN (the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) of a proposed new round of new-gTLD (generic top-level domain) applications to launch in Q2 2026[1], we consider what this second phase may look like, based on comparison with trends and observations from the previous first round[2].

The original new-gTLD programme launched in 2012, to add a series of new TLDs (domain-name extensions) to the Internet’s Root Zone. This is the highest level of DNS (Domain Name System), and the basis for domain infrastructure. The aim of doing so was to “enhance innovation, competition and consumer choice”[3],[4]. As part of this programme, entities were invited to submit applications to act as registries for new TLDs. This would involve being responsible for maintaining the infrastructure, processing applications, and dealing with disputes for new domains across the extension in question. Following the first round of applications in 2012 – during which around 2,000 TLDs were proposed – and a subsequent period of assessment, the first new-gTLDs were delegated (added to the Root Zone) in October 2013. The new registries were categorisable either as open (generally available for domain registrations), restricted (in which particular criteria had to be met for registrations to be permitted), or closed. The TLDs themselves are also grouped into types, with classes including generic, geographic, community, and brand, depending on their intended use. In some cases (in the case of brand TLDs), brand owners have chosen to register their brand name as a domain-name extension and maintain control of the TLD, so as to centralise ownership of their official websites and reduce customer confusion – so-called instances of ‘dot-brands’[5].

Broadly, the intention of the new-gTLD programme was to reduce infringements and build clarity for customers through the use of descriptive TLDs for websites. There were certain restricted extensions including .bank and .insurance[6]. As part of this initiative, the TMCH (Trademark Clearing House) scheme was introduced. This meant brand owners can submit their trademarks for validation, granting them automatic rights to register the trademark as a new domain name upon the launch of a new TLD, and receive notice of any (exact-match) applications by third parties[7]. In addition, some new-gTLD registry organisations also offer blocking programmes (such as the Domain Protected Marks List originally offered by Donuts[8]) which can be employed by brand owners.

However, as with the legacy TLDs, many of the new registrations were associated with abuse, through a range of different types of infringement from cybersquatting and brand impersonation, to phishing and malware distribution. Indeed, many of the new-gTLDs were found to be disproportionately more affected by infringements, despite in many cases having improved enforcement processes in place.[9],[10] This was often a reflection of low-cost registrations with lax requirements.

Even putting nefarious uses to one side, another area of interest for brand owners was the issue of disputes over control of the TLDs. One such example was the case which saw e-tailer Amazon engage in a seven-year legal battle with eight Latin American governments to claim rights to the extension .amazon, which was eventually won by the Amazon corporation[11]. It will be interesting to see how many such conflicts arise this time around, particularly given the market saturation and crossover of brands in the online world.

The history of phase one

Altogether, a little over 1,200 new-gTLDs[12] have been delegated since the start of the programme. Just over half of those have passed through the start of their sunrise period[13],[14] (the initial launch phase, prior to General Availability, when brand owners are able to apply for new domains) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Growth in the cumulative number of new-gTLDs since the start of the programme

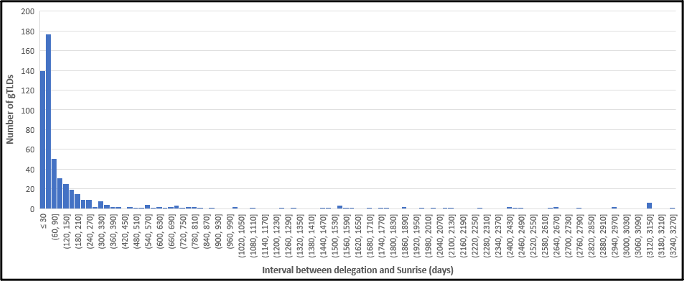

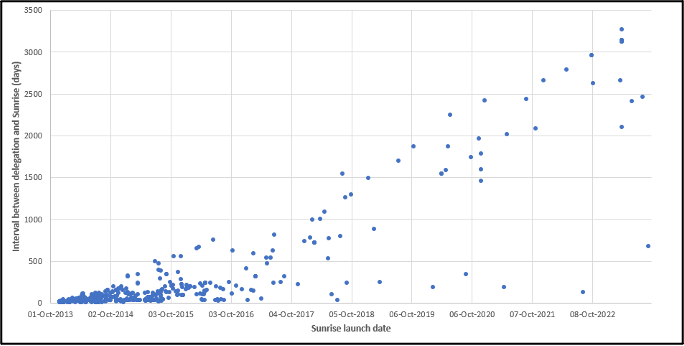

For most of the new-gTLDs, the interval between delegation and sunrise was less than a year, although there is a long tail of cases in which this period was significantly greater. Overall, the vast majority of new-gTLDs were delegated within the first three years of the programme, with many of those TLDs to have sunrised most recently therefore having seen extensive periods of time elapse since their initial delegation (Figures 2 and 3). In some cases, these delays may represent prolonged negotiations or discussions over the management or use-cases of the TLDs in question.

Figure 2: Histogram showing the distribution of intervals between delegation and sunrise, for all sunrised new-gTLDs

Figure 3: Scatter plot of sunrise launch date against interval between delegation and sunrise, for all sunrised new-gTLDs

It is also informative to consider the registration pattern over time of currently-registered domains across a specific new-gTLD, from the time of its launch. An example for a typical representative TLD[15] is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Growth over time in the number of registered domains across the .blackfriday new-gTLD

This pattern is consistent with those noted in previous studies, where an initial spike of activity immediately following the launch of a new TLD is common[16].

Conclusion

Based on observations from the first phase of the new-gTLD programme, we might expect to see some of the same trends in the second phase, leading up to the application period in 2026 and beyond. This includes the possibility of significant numbers of new applications, in some cases by multiple entities, potentially leading to disputes and negotiation.

Brand owners may consider applying to run their own dot-brand extension, depending on characteristics of their IP portfolio and the new-gTLD application requirements as they evolve. Whilst an expensive and technically-complex prospect – often requiring partnership with an enterprise-level domain registrar – it can bring extensive benefits regarding the ability to control all official websites and distribution channels. In any case, organisations are well-advised to take advantage of programmes such as the TMCH and other blocking schemes, to defend their IP and receive early warning of potential infringements.

The speed with which new registrations can take place after the launch of a new gTLD also highlights the importance for proactive real-time monitoring of new registrations, using an automated solution which is capable of covering new domain extensions as they become live. This monitoring should be accompanied by a comprehensive approach to enforcement against identified infringements, as part of a holistic brand-protection programme.

Web3 should also not be overlooked, with generic extensions and options for dot-brands already available within the blockchain domain ecosystem. Indeed, there is an argument that if a brand owner is intending to move from .com in order to future-proof its online identity, it might make more sense to invest in emerging technologies and media such as blockchain domains.

[1] https://www.icann.org/newgtlds-next-round-en

[2] Figures correct based on numbers of new-gTLDs and domains registered as of 02-Aug-2023

[3] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/about/program

[4] https://icannwiki.org/New_gTLD_Program

[5] ‘Brand Protection in the Online World: A Comprehensive Guide’ by David N. Barnett – Box 2.4: ‘Brand protection and the new-gTLD programme’

[6] https://support.tppwholesale.com.au/hc/en-gb/articles/360008969518-Restricted-New-gTLDs

[7] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/about/trademark-clearinghouse

[8] https://www.trademark-clearinghouse.com/content/donuts-dpml

[9] https://circleid.com/posts/20230117-the-highest-threat-tlds-part-2

[10] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7d16c267-7f1f-11ec-8c40-01aa75ed71a1

[11] https://www.ft.com/content/c8f227e6-7b0c-11e9-81d2-f785092ab560

[12] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/program-status/delegated-strings

[13] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/program-status/sunrise-claims-periods

[14] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/program-status/statistics

[15] In this analysis, we consider registrations across the .blackfriday TLD, taken to be a representative example of a typical new-gTLD for a number of reasons:

- It is a small- to medium-sized TLD, having seen around 1,000 registrations since its launch (compared with a median value, across all post-Sunrise new-gTLDs of around 7,700)

- ‘blackfriday’ is a general term relating to e-commerce, lending it both to legitimate use and abuse by infringers

- It is possible to extract domain registration dates in bulk via automated look-ups

[16] https://circleid.com/posts/20220218-domain-registrations-associated-with-new-tld-launches