In our previous analysis[1] of the new-gTLD programme – the gradual launch of new domain-name extensions which commenced in October 2013 – we took a look at what might be expected in the new round of applications set to begin in 2026. In this follow-up, we conduct a retrospective review of the current[2] state of the new gTLD landscape.

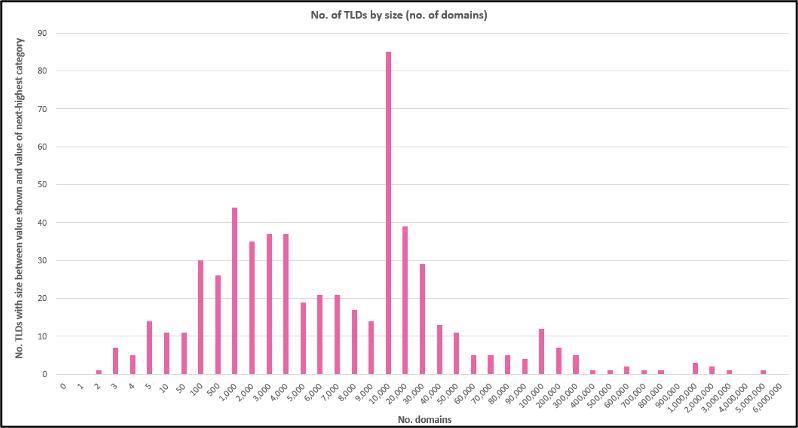

As of the end of November 2023, 583 new-gTLDs have passed through the start of their sunrise periods, the first part of the launch of a new domain-name extension, after which brand owners are able to apply for domains. The popularity of individual TLDs varies greatly, with some having seen only a handful of registrations, but with the largest extensions accounting for several million domains (Figure 1 and Table 1).

Figure 1: Numbers of new-gTLDs by TLD size (measured in numbers of registered domains)

|

New-gTLD extension |

No. registered domains |

|

top |

5,208,791 |

|

xyz |

3,342,289 |

|

online |

2,896,998 |

|

shop |

2,002,143 |

|

site |

1,428,703 |

|

store |

1,353,876 |

|

app |

1,320,994 |

|

vip |

827,725 |

|

dev |

797,403 |

|

club |

615,342 |

Table 1: Top ten new-gTLDs by TLD size (measured in numbers of registered domains)

The greatest concentration of new-gTLDs occurs at a size range of between 10- and 20,000 domain registrations.

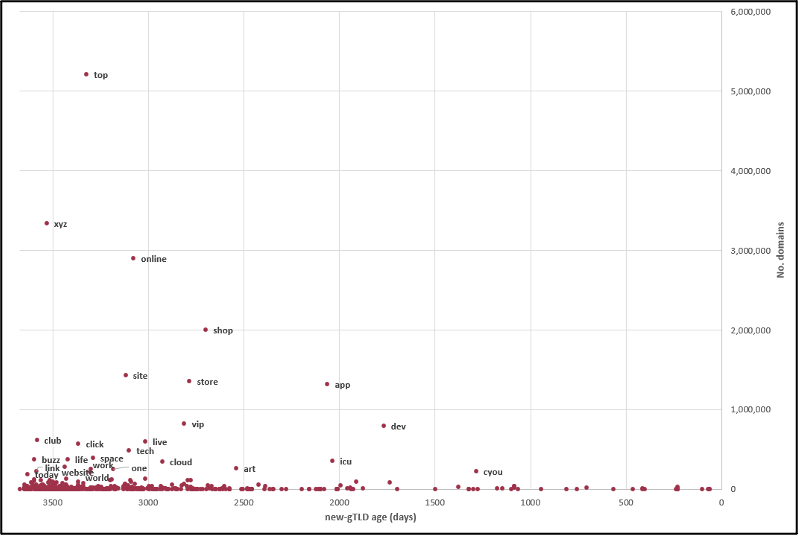

If all new-gTLDs saw a consistent rate of uptake of new registrations, we would expect the older extensions (i.e. those launched nearer the start of the new-gTLD programme) to account for the largest numbers of domains overall. A corresponding analysis is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Scatter plot of new-gTLD size (number of registered domains) against age (days elapsed since start of sunrise period[3]; oldest TLDs to left)

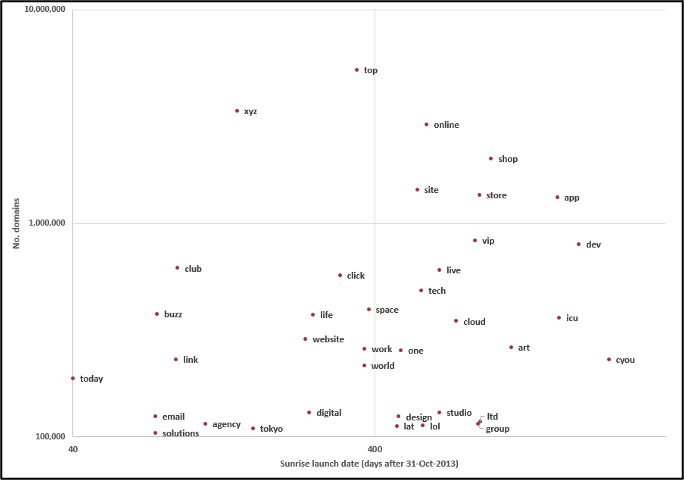

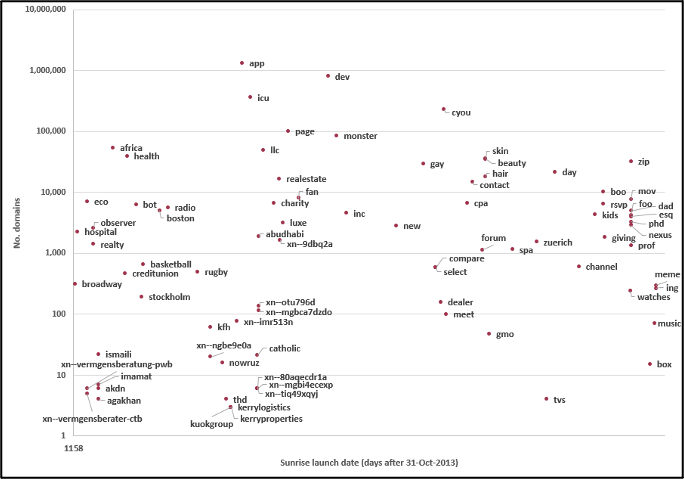

More detailed views of this data, focusing on the largest new-gTLDs (Figure 3) and those registered most recently (Figure 4) are shown below.

Figure 3: (Log-log) scatter plot of new-gTLD size (number of registered domains) against date of start of sunrise period (measured in days since 31-Oct-2013), for all new-gTLDs with more than 100,000 domain registrations

Figure 4: (Log-log) scatter plot of new-gTLD size (number of registered domains) against date of start of sunrise period (measured in days since 31-Oct-2013), for all new-gTLDs registered since the start of 2017

Though there is some suggestion (Figure 2) that the most popular TLDs tend to be amongst the oldest, there is overall no strong correlation between new-gTLD age and size, suggesting that the extensions do not all attract registrations at the same rate. There are a number of reasons why this is the case, with the main points being that the new-gTLDs vary widely in terms of their availability (some, such as ‘dot-brands’, are entirely under the control of the brand owner and are not available for general registration, and others also have stringent application requirements), registration cost, and intended use-case.

Overall, these factors have an impact on the desirability of domains to the full range of online users, including bad actors. It is fair to say that new-gTLDs have not been adopted – for legitimate use – to the extent planned when the programme launched with the intention of adding clarity to the domain-name landscape. Instead, many of these new extensions have been disproportionately utilised for fraudulent purposes, despite many of the new registries implementing improved enforcement processes. This disparity has resulted – at least in part – from the low costs of, and relatively lax requirements for, domain registrations across the new extensions in many cases[4]. Indeed, many of the most popular new-gTLDs (notably .app, .dev, .top, .page (with just under 100k domains, at 99,499), .buzz, and .cyou), appear in the top thirty highest threat TLDs (reflecting association with spam, phishing and malware distribution) overall[5]. Other extensions within the set, such as .xyz, are also notorious for association with abuse[6].

Of course, not all new-gTLD use is fraudulent, and we also see in the set of largest extensions a number of examples which provide insight into the most popular use-cases. For example, the presence of .site, .store and .shop in the list of top extensions suggests that the new-gTLDs are a popular choice for e-commerce sites, and the inclusion of .app is consistent with the growth of mobile technologies.

We also see some interesting ‘clusters’ of related domain extensions (Figure 4), with .skin, .beauty and .hair all released on the same day (01-Dec-2020) and having achieved similar levels of adoption (36k, 35k and 18k registrations, respectively). Conversely, there are also examples of new-gTLDs which are similar to each other but have seen differing popularity, such as .adubhabi and its IDN[7] equivalent (.ابوظبي, or . xn--mgbca7dzdo), both registered on 21-May-2018, but with 1,884 and 116 registrations respectively.

Amongst the most recent launches, we see (somewhat concerningly) some of the greatest popularity for .zip and .mov, extensions which are of possible concern by virtue of the security risks presented by the possible confusion with filename suffixes[8]. It is also notable that there has, as yet, been negligible uptake of .box, despite their compelling description of an innovative dual Web2 / Web3 offering[9],[10]. It appears that the launch of the extension has not yet progressed beyond its closed beta phase[11], although it is possible for customers to submit applications for new registrations for $120/year.

Overall, brand owners are advised to keep a close eye on the new-gTLD landscape, particularly in view of the new set of applications scheduled to launch in the next couple of years. Some may find it advantageous to consider applying to run their own branded extension, but all stakeholders should monitor the emerging landscape, consider their defensive registration strategy, take advantage of any available blocking systems for brand terms comprising protected IP, and implement proactive monitoring and enforcement programmes for new registrations as they arise.

[1] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/the-new-new-gtlds

[2] All analysis is based on the versions of the ICANN domain zone-files downloaded on 21-Nov-2023.

[3] https://newgtlds.icann.org/en/program-status/sunrise-claims-periods

[4] https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/7d16c267-7f1f-11ec-8c40-01aa75ed71a1

[5] https://circleid.com/posts/20230117-the-highest-threat-tlds-part-2

[6] https://silicon.nyc/xyz-domain-problems-spam/

[7] ‘IDN-tifying trends: insights from the set of non-Latin domain names’, forthcoming Stobbs e-book

[8] https://www.iamstobbs.com/opinion/un-.zip-ping-and-un-.box-ing-the-risks-associated-with-new-tlds

[9] https://comlaude.com/launch-of-box-music-bot/

[11] https://twitter.com/boxdomains/status/1712809326925197518

Send us your thoughts:

Would you like to read more articles like this?

Building 1000

Cambridge Research Park

CB25 9PD

Fax. 01223 425258

info@iamstobbs.com

Privacy policy

German office legal notice

Cookie Declaration

Complaints Policy

Copyright © 2022 Stobbs IP

Registered Office: Building 1000, Cambridge Research Park, Cambridge, CB25 9PD.

VAT Number 155 4670 01.

Stobbs (IP) Limited and its directors and employees who are registered UK trade mark attorneys are regulated by IPReg www.ipreg.org.uk